VICENZA, Italy — He was a penniless, traumatized Vietnamese teenager with a fifth-grade education when in 1980 he arrived in the U.S. He knew how to survive in the jungle, evade checkpoints and control the terror he often felt.

But he couldn’t speak more than a few words of English and had little practice in how to live a regular life.

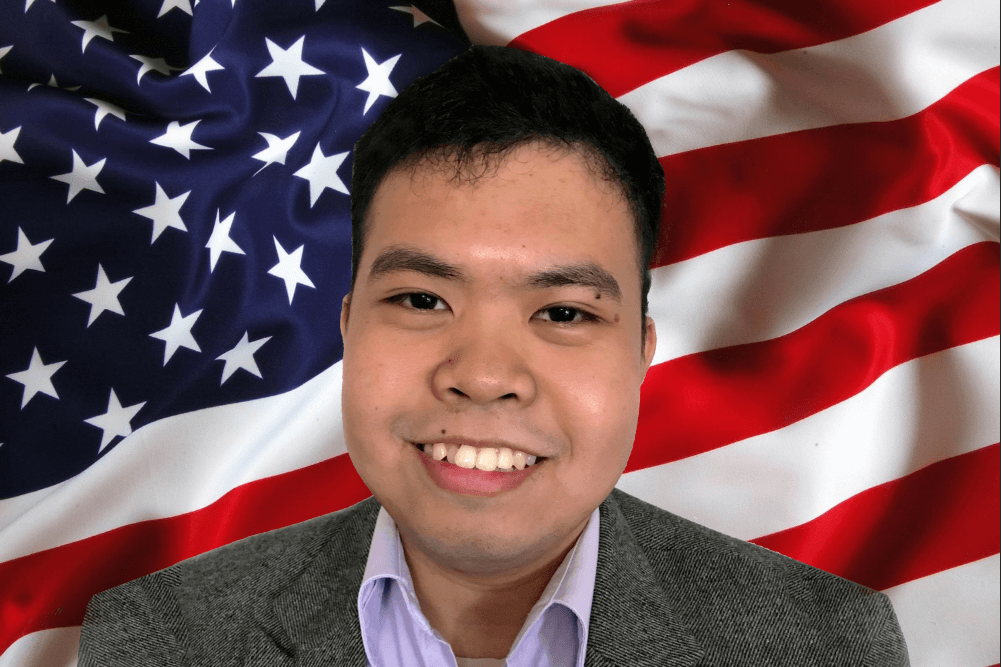

Yet within seven years after his American arrival, Lap The Chau had a new name, a degree from the Virginia Military Institute and a career as “an officer in the greatest Army on Earth,” as he put it.

Brig. Gen. Lapthe Flora, as he’s now known, is deputy commander of U.S. Army Africa and assistant adjutant general of the Virginia National Guard.

He is thought to be the only Vietnamese “boat person” to become a general officer in the U.S. military.

Lapthe C. Flora is promoted to brigadier general at the National D-Day Memorial June 6, 2016, in Bedford, Va.

COTTON PURYEAR/VIRGINIA NATIONAL GUARD

“After what I went through, practically death, and then somebody gives you that opportunity to live again, I can only say from my own perspective that I’m very grateful for what this country has done for me,” Flora said in an interview with Stars and Stripes.

Flora, who in civilian life is an engineer holding several patents on night-vision goggles, has recounted his unlikely story many times.

“The possibility in this great nation is boundless; the American Dream is real, only if you dare to pursue it with laser-focused hard work and perseverance,” Flora said in speech when he was promoted to brigadier general more than two years ago.

He has also showed appreciation for those who helped upon his arrival in America.

“There’s no one who can get to where they are on their own. You need help,” he said in a 2017 talk at the Raleigh Court United Methodist Church in Roanoke, Va.

Audrey and Jack Flora, from Roanoke, Va., adopted Lap The Chau.

COURTESY LAPTHE FLORA

The church had sponsored him and several family members in 1980.

“We had a house for them. They came with nothing,” said Sharon Alexi, a former kindergarten teacher active in the church, who helped settle the 11-member Chau family.

She helped teach Flora and his brother English and how to drive.

“They caught on very quickly,” she said. “It was fun. It was a joy.”

A couple in the congregation were so taken with Flora that they adopted him when they were in their 60s and he was either 21 or 23; his birthdate is uncertain.

“People thought they were crazy,” Flora said. “But they took me in.”

Postwar exodus

Flora is among 800,000 people who fled Vietnam by sea starting in 1975 in an international humanitarian crisis that took years to resolve. The exodus reached its height in 1978, when some 5,800 refugees a month were landing in Asian countries increasingly unwilling to accept them and an untold number were dying at sea.

President Jimmy Carter responded by ordering U.S. ships to the rescue, then doubled the number of refugees accepted into the U.S. from 7,000 to 14,000 a month, despite polls showing a majority of Americans disapproved.

“I benefited greatly from the U.S.’s decision to accept me into this country,” Flora said. “I’m extremely grateful for the circumstances that led to my citizenship.”

Flora declined to imagine what might have become of him had the Carter administration decided not to accept Vietnamese refugees.

Brig. Gen. Lapthe Flora and his wife, Thuy — pictured with their daughter Christine — were both Vietnamese refugees when they arrived in the U.S.

COURTESY LAPTHE FLORA

In the end, nearly all of his family arrived in the U.S., including his future wife, his mother and a long-lost sister who’d been given up for adoption in Vietnam.

“I don’t like to think about hypothetical paths my life could’ve taken,” Flora said. “Instead, I focus on the future and my ability to give back whenever possible and sharing my story to inspire others.”

That story includes many early hardships and eventual triumphs.

When he was 2, his merchant marine father was killed in a mortar attack, Flora said. The death plunged the ethnic Chinese family into poverty so severe that his mother gave her infant daughter to another couple.

At 11, as the Vietnam War raged throughout the countryside, Flora worked as a live-in servant at a factory. That ended on April 30, 1975, when the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong captured Saigon, South Vietnam’s capital, ending the war and turning all of Vietnam into a socialist, one-party state.

The new communist government instituted “re-education camps” and other repressive measures against political opponents and those who had collaborated with the Americans.

The boy who would become U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Lapthe Flora, left, poses with his family in Vietnam. All of them eventually fled the country as refugees.

COURTESY LAPTHE FLORA

Flight to freedom

Flora and two brothers fled the fallen capital, renamed Ho Chi Minh City, where they were at risk for military conscription. Hiding in the countryside for three years, he said, they survived on crops they planted and animals they hunted, including lizards and porcupines.

The brothers were sometimes frightened and often hungry, but they were also free.

“We sang in the middle of the night,” Flora said. “It was kind of fun.”

His escape came after a sister and brother-in-law in 1979 secured 11 spots for the family on a cramped, fetid fishing boat. The terrifying voyage lasted five horrible days and nights, he said, with little food or water, vulnerable to storms, shipwreck and pirates. A toddler on board died before they landed in Indonesia.

“We knew there was less than a 50 percent chance of survival,” Flora said. “Desperation, destitution will drive people to do anything.”

Lap The Chau was a destitute teenager in 1979 when he escaped Vietnam as a ”boat person” and was photographed at an Indonesian refugee camp. He’s now Brig. Gen. Lapthe Flora.

COURTESY LAPTHE FLORA

Much of his family settled in California, which along with Texas, accepted the most Vietnamese refugees.

But he preferred Roanoke and life with his adoptive family, Jack and Audrey Flora.

He graduated from high school in three years, while working part-time bagging groceries, and was accepted to VMI.

He took to the spartan school, his adoptive father’s alma mater, saying it reminded him of his early schooling in Vietnam.

He’s encountered little discrimination since coming to the U.S., he said, and any slights are easily ignored.

“You feel sorry for their narrow-mindedness,” Flora said.

From the start of his military career, Lapthe Flora made an impression. As a young lieutenant with the 116th Infantry Regiment in 1991, when Capt. Eric Barr met him, it was clear it wasn’t just his backstory that made him unique.

Lapthe Flora took to the rigors of the Virginia Military Institute, saying the military academy reminded him of his strict elementary schooling in Vietnam. He is pictured here as a cadet in an undated photo.

COURTESY LAPTHE FLORA

“It just jumped out at me that Lapthe was one of the most professional, squared-away officers,” Barr said. “It was just obvious he knew his business.”

On a 2007 deployment to Kosovo, “whenever something really tough came up, Lapthe was known as the go-to person,” said Barr, now a retired colonel.

“Where it really stood out, he had so much credibility with the Serbs and the Albanians because they knew he had lived their lives,” Barr said. “He had been through the same hell they had been through.”